Educate & Vaccinate

Spreading the word about HPV’s Highly Protective Vaccine

Written by Steve Sandstrom

Published in Aspects Magazine, Autumn 2017 (40-4)

The human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world. It can cause genital warts, anal cancer and cancer of the mouth and throat (oropharyngeal cancer)regardless of gender. It can also cause cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina and of the penis. In 2012, about 528,000 new cases and 266,000 deaths occurred from cervical cancer worldwide.

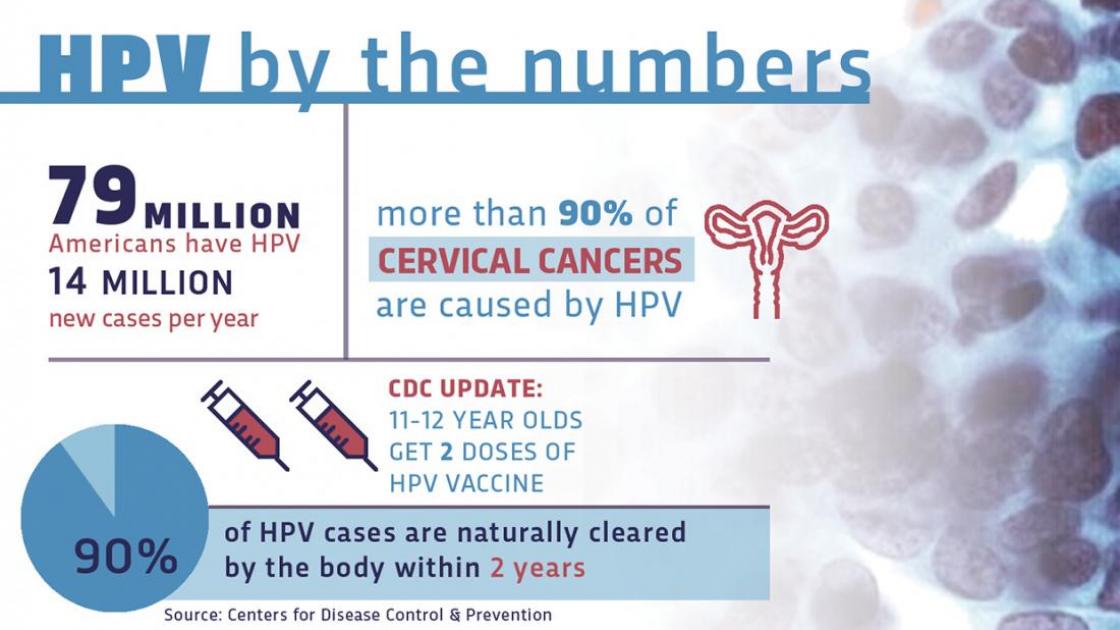

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than half of all sexually active people will contract one of the viruses during their lifetime. About 14 million Americans, including teens, are infected by HPV every year. Most infections go away on their own without causing serious problems. But in some people, an HPV infection persists and results in warts or precancerous lesions that increase the risk of cancer.

Now the good news: There’s a vaccine to prevent HPV. It’s been in use for more than a decade and has proven to be both safe and incredibly effective. It’s approved by the FDA and recommended for children ages 11-12, before they become exposed. It can be given beginning at the age of 9, up through age 26. Since its introduction in 2006, there’s been a 64 percent reduction in HPV infection among teenage girls.

Yet, the vaccine has faced some resistance from a group that seem antithetical to protecting children: parents.

SIU Medicine is one of many institutions striving to educate caregivers and colleagues alike, in an effort to increase awareness about the intrinsic value of the HPV vaccine.

Researchers have determined there are more than 170 types of human papillomavirus. Over 40 of them can be transmitted through sexual contact. Luckily, only around a dozen – known as ‘high risk’ types – are linked to cancer. Risk factors for persistent HPV infections include an early age of first sexual intercourse, multiple partners, smoking and poor immune function.

Laurent Brard, MD, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, remembers hearing about the clinical trials for the HPV vaccine in 2002, while in his first year of a gynecologic oncology fellowship at Brown University/Women and Infants Hospital in Providence, RI (WIHRI). About an hour away in Kingston, the University of Rhode Island was being used as one of the sites for the HPV vaccine trial. Following FDA approval of the first HPV vaccine, Gardasil in 2006, Dr. Brard’s gynecologic oncology group at WIHRI was so excited about the potential benefits of this new vaccine that they organized weekend clinics to vaccinate young women.

Now chief of SIU’s Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Brard points out that gynecological oncologists are not primary care doctors. “We’re traditionally on the treatment end for women who have cervical cancer, so this was a big opportunity for us to be involved on the preventative medicine side. It was great for our patients, and we thought it might encourage others, too.”

Once trials completed, the Gardasil 4 HPV vaccine was licensed in June 2006 for females and in 2009 for males. Cervarix was introduced in 2009 as an alternative for females. It targets HPV types 16 and 18 that cause about 70 percent of cervical cancer cases and most HPV-induced genital and head and neck cancers. Gardasil 9 went into use in December 2014 for both male and females and covers about 90 percent of the viruses. New vaccines are currently in development that offer even more protection.

The HPV vaccine was warmly welcomed within the medical community. However, as it came onto the market, other voices were questioning the overall safety of vaccines. Back in 1998, British physician Andrew Wakefield had written a paper connecting bowel disease and autism to the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. In it, he alleged the vaccine hadn’t been properly tested before being put into use.

The Lancet, the journal that originally published Wakefield’s work, stated in 2004 that it should not have published the paper and formally retracted it in 2010, after the British General Medical Council ruled Wakefield had falsified data in hope of financial gain. But the damage had been done. That one article set off a wave of fear that has helped convince thousands of people that vaccinations are dangerous. Some celebrities added fuel to the controversy, speaking out against the safety of vaccines. At the same time, the internet was expanding its reach into homes, offering easy access to reputable medical websites with sound research, but just as often spreading misinformation through social media and sites of questionable sources.

With the public concerns surrounding the HPV vaccine, the CDC’s post-licensure safety monitoring has been intense. The Vaccine Safety Datalink program at the CDC closely monitors all vaccines, including the HPV vaccine, for any side-effects. More than 80 million doses of the vaccine have been given in the US alone without any significant problems. Likewise, a 2013 study of nearly a million girls in Denmark and Sweden determined the HPV vaccine was not linked to any short- or long-term health problems.

Careyana Brenham, MD, associate professor in SIU’s Department of Family and Community Medicine, understands some of this hesitancy here in the states. “We’ve been providing the vaccine for about 10 years now. It’s still new enough that it makes some parents uncomfortable. They wonder if they should do it or not, and they want to hear more. What they hear from other patients and in the media sometimes, no matter how unjust it is, plants doubts. All the published literature about vaccines and autism shows that there is no link between the two.”

Craig Batterman, MD, associate professor of pediatrics, concurs. “My partners and I have all encountered resistance. The first step is to dispel the misinformation, which is formidable. Media figures and websites have spread so much rumor and innuendo that it takes time to counter that with facts. Once that has been discussed, we need to discuss the real reason for the vaccine, which is cancer prevention.”

Australia has set the benchmark for successful national HPV vaccinations. The country was one of the first to establish a nationally financed HPV vaccination program for girls and young women. It has also seen a decrease in the number of cases of cervical abnormalities, a precursor to cervical cancer.

Australia offers free HPV vaccination to girls and boys who are 12 and 13 years old, and catch-up programs for those under 26. The vaccine is typically administered in three doses, beginning around age 12. In 2010, coverage rates for girls that age in Australia’s school-based programs reached 83 percent for the first dose, 80 percent for the second dose and 73 percent for the third. The findings suggest that Australia’s program has experienced little of the resistance that has stymied vaccination efforts in the US. Presently, only Rhode Island, Virginia and the District of Columbia have mandated the vaccines for schoolchildren.

Another barrier for parents may be uneasiness toward their child’s eventual sexual activity. “When we’re giving the HPV vaccine at the age of 11, some parents think we’re doing it because their children are going to become sexually active soon, which is not the case,” says Brenham. “We want the vaccine in long before the children become interested in sex, so they can have a robust immune response should it ever be needed.”

But since the vaccination is around the age that parents and schools begin to teach students about reproduction and health, the connection is already there. Brenham says, “It’s similar to the false adage in some parents’ minds that if you give a child birth control, they’re going to start having more sex. Statistics don’t support that. But it’s enough to make parents think, ‘I’ll just wait a while.’”

Waiting is another concern, because missed opportunities during routine visits can undermine the vaccine schedules a family should follow. Presently, children are required to receive vaccines as newborns, before kindergarten, before sixth grade and before they start high school. Physicians try to group vaccines within these windows. Dr. Brenham says, “The optimal time to catch them is when the child is still at home with their parents and making regular visits to their provider to keep current on the school’s vaccine requirements. It’s a great opportunity for education, and you can also help talk through any concerns the parent or child has.”

“I tell residents that it’s best to do it while the child is here now, because if they stay healthy they might not come back until they’re in high school. I have them say, ‘Since we’re getting two, it’s easy to do three.’”

Because older children tend to become more apprehensive about shots, Brenham has another motivator for parents to consider. “If the HPV vaccine is administered by the age of 12, only two shots are required. If it’s begun after the age of 15, three are recommended. So if you’ve got a child who doesn’t like getting shots, it’s to their benefit to get them in sooner rather than later.”

Brenham feels sensitivity is important, but so is brevity. “I tell my residents that we’re recommending these three vaccines at this time, and not to single one out. If Mom has questions, I’ll talk about the way each is transmitted, again without emphasizing one over another. If they hone in on HPV, I tell them it’s transmitted the same way as hepatitis B, which is another shot their child has already received, and that we really advise getting these together many years before the child is likely to face exposure,” she says.

Some mothers know the value in the vaccine firsthand, says Dr. Brenham. “I’ve had a lot of female patients who’ve had abnormal pap smears tell me, ‘I want my daughter to get the shot. I do not want her to go through what I went through.’ And they’re quicker to vaccinate their boys, too. There’s a population of parents out there who know what this virus does and they are eager to have their children protected.”

Brenham says it’s not unusual for providers to get asked, “What would you do for your child?” She says, “I can easily relate to them in my doctor-patient role and advise them of the value of this vaccine as a doctor who treats children. And then I can take a step back, and relate to them personally, as a mom. My three oldest daughters have been vaccinated.”

Initially, the link between cervical cancer and HPV was discovered, so immunizing girls became priority number one. Adding boys was seen as useful for the herd immunity. But now research has linked different HPVs to cancers that affect men, and the vaccine is warranted for their specific protection.

For instance, approximately 70 percent of HPV-related head and neck cancers occur in men. It’s likely due to a combination of factors relating to differences in anatomy and immunology between men and women, says Arun Sharma, MD, a head and neck surgical oncologist with Simmons Cancer Institute (SCI). His patient, Mark Waldhauser, 47, was diagnosed with cancer in his neck in April 2016. Unlike most men, he didn’t notice it shaving; he discovered it while sitting in a meeting. He wasn’t a smoker. His primary doctor investigated and ruled out other things before a biopsy showed he had stage 4 throat cancer.

“It’s tough to hear ‘stage 4,’” Waldhauser says. “Sometimes you don’t even hear what comes after that. My fiancée who works at SIU was in there with me. She heard ‘stage 4’ and I heard ‘treatment,’ so we balanced each other out.” Dr. Sharma met with Waldhauser and performed transoral robotic surgery (TORS) on June 10. The surgery goes through the patient’s mouth to minimize damage to tissue and the swallowing process.

Unfortunately, the HPV that causes head and neck cancer can go dormant for long periods. “Usually, people are first exposed to it in their teens or twenties,” Dr. Sharma says. “Most of the men getting an HPV-associated throat cancer are in their 40s, 50s and 60s, so there is a timespan of decades between exposure and clinically evident cancer.” Although the exact steps between HPV infection in the throat and development of oropharyngeal cancer aren’t as well understood as the sequence of events in cervical cancer, the HPV vaccine would block that hidden threat, once and for all.

Working with researchers at SIU and the Siteman Cancer Institute at Washington University in St. Louis, Dr. Brard has been studying the differences in cancer rates in downstate Illinois. “There is a higher rate of cervical cancer in rural communities and within lower socio-economic populations,” he says. “There are many causes, but a big obstacle is communicating about the vaccine. We’re going to need to study further to find out how to change that.”

SIU Medicine’s physicians and educators are continuously working to increase the vaccination rates in the service region. SCI holds both public and professional events to educate audiences on the benefits of the HPV vaccine. Outreach coordinator Kristi Lessen and Cindy Davidsmeyer, SCI’s director of community support, have been actively promoting HPV awareness at health fairs and workshops for years.

Encounters with receptive parents and other advocates buoy their spirits as they get the message out. Davidsmeyer says her OB-GYN was an early supporter of the vaccine and both her daughters were vaccinated. Lessen was delighted her new dentist did a thorough head and neck cancer screening on her while she sat in the chair. Dentists and dental hygienists are part of the multi-disciplinary approach to detecting and preventing oral and throat cancers.

Speaking at one of SCI’s educational conferences earlier this summer, Rachel Caskey, MD, MPP, said that overcoming the barriers to vaccinations will require a combined effort between parents, physicians and community stakeholders. Caskey is a pediatrician at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine and School of Public Health who became a health services researcher to improve national vaccination efforts. “It takes a village. We need to get our act together as a society and get more creative in health care. The countries that have been most successful are vaccinating kids at school, as we used to do with polio.”

At the same meeting, Gina Lathan, immunizations section chief at the Illinois Department of Public Health, focused on framing the message. “The challenge is to normalize the subject so that it gets greater traction with families. We want vaccines to be brought up when the children are young, when it can do the most good, and become part of the overall health plan: diet and exercise, safety in the neighborhoods, etc. We need to make sure it becomes a part of the conversation,” she said.

“And we need to have more conversations outside of health care spaces, in schools, churches, community centers. Let’s help make it understood throughout the community.”

Dr. Brenham sees this team approach to research, health care and outreach leading in one direction. “During my time in medicine there’s been a huge improvement in women’s health through cervical cancer screening. When I was a resident we were doing pap smears every year on teenagers. Now we’re doing pap smears every three or five years, and colposcopies are much less common.”

“I remember when I was in high school, my dad who was a family physician talking to us and saying they’d just discovered that cervical cancer may be related to sexual activity. That those who had a higher number of partners were at greater risk. But once we focused on the virus itself, we pinned it down to types and developed a vaccine against it. Now we’re giving children these vaccines and we’re seeing the decreased rates of cancer as a result. It’s amazing what the medical community has been able to do,” she says.

“Imagine eliminating a type of cancer. That’s a pretty significant thing, and I really believe we could see it in my lifetime.”