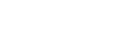

Reflections of a Military Doctor

Dr. Sean Hollonbeck reflects on medical muses, from his twin brother's accident, equine therapy and consulting on 'Black Hawk Down'

Written by Ann Augspurger

When Col Sean Hollonbeck, MD, ’97 was a high school sophomore in Rochelle, Ill., he started a spreadsheet on the pros and cons of active versus reserve duty and spent a whole year researching possible career paths in the military. While most classmates were more concerned about what goes on under the Friday night lights (although Hollonbeck also played football) or the current condition of their complexion, he was calling military recruiters and interviewing them about the ins and outs of serving. Hollonbeck recalls they would push back and say things like, “Son, it doesn’t work like that.” But the young and determined Hollonbeck didn’t really care how it worked. He persevered.

When Col Sean Hollonbeck, MD, ’97 was a high school sophomore in Rochelle, Ill., he started a spreadsheet on the pros and cons of active versus reserve duty and spent a whole year researching possible career paths in the military. While most classmates were more concerned about what goes on under the Friday night lights (although Hollonbeck also played football) or the current condition of their complexion, he was calling military recruiters and interviewing them about the ins and outs of serving. Hollonbeck recalls they would push back and say things like, “Son, it doesn’t work like that.” But the young and determined Hollonbeck didn’t really care how it worked. He persevered.

Like many youngsters in the throes of deciding what they want to do for the rest of their lives, family influences played a role in Colonel Hollonbeck’s career path. He was born at Fort Benning (Ga.) where his father served in the US Army hospital as an optometrist. When Hollonbeck was still a boy, the family moved to Rochelle in northern Illinois where Sean grew up.

A tragic accident involving his identical twin brother, Scot, also impacted Hollonbeck’s decision to become a physician. In the summer of 1984 (at age 14), Scot was riding his bike to swim practice when a drunk driver struck him in front of their childhood home, leaving him paralyzed. Sean Hollonbeck decided in that harrowing moment that he never wanted to feel that helpless again.

Through the years, the brothers have not let the circumstance break their close, identical-twin bond. Colonel Hollonbeck’s pride in, and respect for, his twin come up early and often in conversation. His rate of speech and the pitch of his voice pick up a bit when he speaks about Scot, who is an avid wheelchair racer. In fact, Scot Hollonbeck has competed in four Olympic and Paralympic games, earning two gold and three silver medals in the ‘90s at the Barcelona and Atlanta games.

Applying a Scientific Approach

Hollonbeck applies a scientific approach to all his life experiences whenever he can. For instance, while he believes in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS) (he advocates dropping the “D” for disorder), he says there are alternative therapies that need to be both considered and researched. He grew up around horses and is a believer in utilizing equine therapy.

“I did research on several types of equine therapy programs, and none of them are validated,” so he spent time off the clock researching programs in the U.S. and abroad. He presented his findings to the Joint Program Committee (JPC) on Military Research and his work made it to final selection. In fact, he is so passionate about the benefits of equine therapy that he has purchased land near Pensacola, Fla., and already has a herd of horses and even a Jerusalem donkey. He intends to offer equine therapy on a part-time basis in his impending retirement, scheduled for the summer or early fall of 2018.

He explores supplemental or alternatives to CBT because “I don’t sleep very well at night,” Hollonbeck admits. “When you see and live through trauma, I don’t care if you’re a nurse, a policeman, or in the military; you survive, but you may remember, and there are challenges to that,” Hollonbeck said. “There is still a big struggle with PTS — in how it is treated and how it is handled and medication/sleep aid sedation is not the answer.”

He is also active in hearing loss research and promotes a common-sense solution: to establish a joint baseline military minimum-hearing-protection-level active device for day-to-day use by service members in continuous noise environments. He points out that civilian recreational shooters use such devices. The laboratory he worked at created a dual-layered device to wear inside helmets called the communications and ear protection (CEP). While on the phone with Hollonbeck discussing his career and his life for this interview, he was waiting in an audiology clinic to get fitted for his third set of hearing aids since the army “didn’t promote hearing protection back then as an infantryman.” He points out that the top two disabilities in the U.S. Veteran’s Administration and the military are tinnitus and hearing loss.

CEP devices have warded off aviation-related hearing loss in the U.S. Army for 20 years now, but the prevention initiative hasn’t been implemented in other areas of the military, he said. As the former auditory protection and performance division chief, as well as the JPC-5 working group chair for hearing loss, he has asked the obvious but unaddressed questions, including “We have a $6 million budget; why do we not have active ear protection in all areas of the military?”

A Rich Military Career

After spending his sophomore year of high school doing his research, he enlisted with the Illinois Army National Guard as a light infantryman at the young age of 17. In college, Hollonbeck’s Air Force ROTC instructor was so impressed by his work ethic and drive, the instructor wanted to send him to ROTC summer camp for further training but there was a wrinkle in that plan: the young Hollonbeck took Air Force ROTC as an elective, which is not a common practice. (At that time he was exploring two career paths in the military: flying versus medicine.) Besides, he already had a summer camp commitment as a light infantryman in the Army National Guard. You could say he navigated the military on his terms.

After graduating from the University of Illinois and then the SIU School of Medicine, Hollonbeck was commissioned in the U.S. Army Medical Corps and completed his residency in Family Medicine at Martin Army Hospital in Fort Benning, Ga., the same place his father served as an optometrist. He continued his medical education with a second residency in the joint Army-Navy Aerospace Medicine at Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Fla., which included a master’s degree in public health. His most recent assignment was Deputy Commander of the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory at Fort Rucker, Ala.

A decorated colonel, he has served three times in OEF (Operation Enduring Freedom) in Afghanistan and twice in OIF (Operation Iraqi Freedom). He first served in Iraq in 2003 and volunteered to go back in 2013. “We helped thousands of people during the 2013 surge,” he said. During his years of service, he and his team provided medical care to al Qaeda, Taliban, Iraqi insurgents, and others, “immediately after they tried to kill you.”

As part of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) “we were not welcome there,” Hollonbeck reflected. “We conducted raids at people’s homes and compounds and they get hurt and we get hurt and we treat them all,” he said.

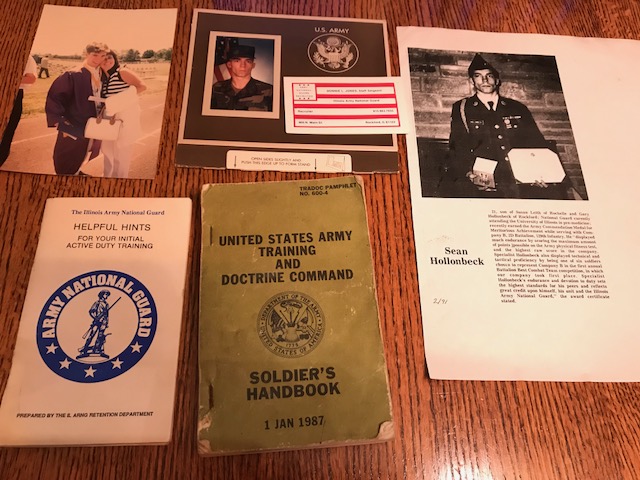

While Hollonbeck chuckles at most of Hollywood’s portrayal of the military, he was invited to offer military medical expertise onsite during the filming of Black Hawk Down in Morocco. In fact, he even got to be an extra in the movie that chronicles the events of a 1993 raid in Mogadishu. So did they get it right in Black Hawk Down? Hollonbeck said they did, adding that the Department of Defense went to great lengths to ensure accuracy in retelling the story. The film certainly “honored men who served and died that day,” Hollonbeck said.

His days at SIU School of Medicine

Colonel Hollonbeck says he remembers receiving the school’s publications Aspects and SCOPE in his care packages when he was overseas and enjoyed staying connected to the school in that way. Hollonbeck said he admires how well-rounded the SIU School of Medicine is and how it “stays true to its roots” in its mission to educate physicians to serve central and southern Illinois “and that was a big draw for me to attend there,” he added.

Always the analyzer advocating change, Hollonbeck believes all medical schools should teach a one- or two-week class that includes some of the same basic and advanced life-saving techniques that the army teaches its medics, PAs and physicians. “I would put my medics up against any doctor out there – except for maybe ER docs–because we’re out there in the dark, working on soldiers on their side, with noise and commotion all around, and we drop lines into extremities and drill right into the tibia and boom(!), we’re in,” he said.

His advice for medical students touches on longevity and self-care, and he likens a career in medicine to a marathon instead of a sprint. “Stay healthy, take time to exercise and pay yourself first,” says the man who is retiring from the military in the same chest and waist size of his very first uniform and sneaks in push-ups and sit-ups in between patient appointments.

As a unit surgeon in charge of all medical training, a flight surgeon, and a physician serving in numerous deployments, Hollonbeck says he feels fortunate to have served. “I realized at a young age we all live in a blessed country, and that country has given a lot to us.”

Hollonbeck’s response to the gratitude he felt and still feels for his country? It all began with action in the form of a spreadsheet. Perhaps his retirement will be filled with much of the same: gratitude and action in whatever form that takes, minus the spreadsheet. Or maybe not.