Leading in turbulent times

In her book Leadership in Turbulent Times, Doris Kearns Goodwin recounts the life stories and presidential journeys of Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson. A major theme of the book is that each of these impactful leaders was forged out of the challenges they faced in their early life, including rejection, failure, loss of loved ones and loss of health, amongst others. The character they brought from these experiences to the unexpected challenges they faced during their presidencies ended up being the resource that made their leadership effective. It seems the pressures we encounter in our personal journeys, and the way we apply the lessons therein learned in times of future challenge, often become the defining moments of our lives.

In times less pressured than the climate we currently find ourselves, we often self-counsel on the importance of reflective activity and taking time in our busy schedules in the health care sector for strategic and generative thinking, recognizing as Covey has outlined that this ‘important but not urgent’ activity is typically the most neglected by all of us, and yet the most predictive of where will be in 5 or 10 years.

Given those reference points, I wanted to offer the following as a brief leadership (i.e., servanthood) reflection for the time in which we currently find ourselves. How can we reflect on and leverage our own character strengths at a time when they are needed? What might our contribution be in a time of challenge, one that might ultimately be looked back upon as healthcare’s “finest hour” for our generation? What matters at a time like this as our healthcare system, economy and way of life are challenged by illness, social isolation and resource limitations much of the world has been used to, but are relatively novel (no pun intended) to us in American healthcare? We would offer three responses.

Compassion and Commitment

First, we can focus on the combination of compassion and commitment. Nearly all of us went into health care in part, if not predominately, so we could pursue a way of life and work that put others’ needs ahead of our own; to make their welfare and thriving the focus of our efforts. At a time such as this, our patients, our colleagues of every description, our neighbors both literally and figuratively, and we ourselves are more than ever in a place of needing to know there is a depth of commitment, colored and textured by genuine compassion, in the interfaces we share. We need to know that this stems from the highest regard for the value of the lives we serve, both the patients before us and the colleagues at our elbows, as well as the families and core relationships that keep us whole and strong. The resolve based in caring that stems from such commitment invites our best service, the “better angels of our natures” as Lincoln referred to, and brings a dimension to our service that takes our humblest deeds and actions and renders them sacred, acts of worth-ship that not only save lives in a biologic sense, but lift hearts and calm fears. We need to be people of such compassion, and such commitment in a time like this.

What Makes Life Meaningful

Second, we need to lean into meaning in a way we societally are not used to, and indeed seem to have steeled ourselves against. Prior to the current pandemic, the average life expectancy in the U.S. had decreased for three straight years. The reason was not worsened outcomes from cancer or cardiovascular disease, nor at that time a new infectious scourge. It was from so-called “deaths of despair,” including suicide and drug-related mortality, and included elements related to the widening disparities in social determinants of health that can dictate an almost 20-year change in one’s life expectancy in three stops on the blue line in Chicago. It seems in our pursuit of the “good life” and the “American Dream” we have lost sight of those elements of life that give it ultimate purpose, significance, value and meaning that stretches beyond death itself. It is apparent that the answers to these issues don’t come with wealth, prosperity or technology, or the nation richest in those domains wouldn’t have been the only developed nation reporting such statistics and outcomes synchronous with our enjoyment of those privileges. Pausing at this time to ask what makes life meaningful, what makes our investments of time and energy worthwhile beyond possessions, resumes and the promise of leisure, is a journey from which we all can benefit, and might make the current crisis a personal and collective societal learning opportunity of proportions that could far outlive, and out-impact the pandemic itself.

Learn from the Past

Third, we can learn from those who have gone before. Recognizing that the current crisis involves a virus we believe is new for our species, it strikes me that we are perhaps distancing ourselves from a wonderful source of hope and perspective when we repeat and recite words like 'novel' and 'unprecedented' in our ongoing conversations and declarations. In a sense, all of history is unprecedented, and will continue to be so. In fact, prior generations have dealt with plagues that ultimately and proportionately claimed more lives than this pandemic will by all current predictions, including bubonic plague and the 1918 influenza. In commenting on this theme in 1948 and the then-relatively new specter of atomic warfare, C.S. Lewis offered the following reflection:

"In one way we think a great deal too much of the atomic bomb. ‘How are we to live in an atomic age?’ I am tempted to reply:

‘Why, as you would have lived in the sixteenth century when the plague visited London almost every year, or as you would have lived in a Viking age when raiders from Scandinavia might land and cut your throat any night; or indeed, as you are already living in an age of cancer, an age of syphilis, an age of paralysis, an age of air raids, an age of railway accidents, an age of motor accidents."

"In other words, do not let us begin by exaggerating the novelty of our situation. Believe me, dear sir or madam, you and all whom you love were already sentenced to death before the atomic bomb was invented: and quite a high percentage of us are going to die in unpleasant ways. We had, indeed, one very great advantage over our ancestors—anesthetics; but we have that still. It is perfectly ridiculous to go about whimpering and drawing long faces because the scientists have added one more chance of painful and premature death to a world which already bristled with such chances and in which death itself was not a chance at all, but a certainty."

"This is the first point to be made: and the first action to be taken is to pull ourselves together. If we are all going to be destroyed by an atomic bomb, let that bomb when it comes to find us doing sensible and human things—praying, working, teaching, reading, listening to music, bathing the children, playing tennis, chatting to our friends over a pint and a game of darts—not huddled together like frightened sheep and thinking about bombs. They may break our bodies (a microbe can do that) but they need not dominate our minds."

While Lewis’ call to “pull ourselves together” may seem a strong admonition for a society facing a very human fear, and particularly so for a health care profession, we see doing exactly that as it is called upon around the world in this time of challenge, his emphasis on “doing sensible and human things” in the face of our fears provides a rubric for engagement at a time when we ourselves, and all around us need our best and deepest presence.

Seeing that other generations have borne their crosses, often greater and with less resources than our own, gives a sense of solidarity and purpose to the current drama as an important act in a much bigger play in which we are all taking part. Indeed, we do not stand alone, in this time, or in the history of our race.

Stepping outside our present context with some good reading, or sharing of stories with some older colleagues or friends, or watching a good documentary or movie that inspires acts of courage in the face of seemingly overwhelming challenge, is a wise way to spend at least some of our time in the present context.

Finally, there is hope. You may know the story of James Stockdale, who was the highest-ranking prisoner of war in the ‘Hanoi Hilton’ during the Vietnam War. He was asked after the war how one survived such an experience, which for him included targeted torture over an 8-year imprisonment and no certainty he would ever be released or see his family again, whilst shouldering the burden of command and seeking to be an inspiration and example to his colleagues suffering similarly. His answer was the ‘Stockdale paradox:’

“I never lost faith in the end of the story… I never doubted that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which in retrospect, I would not trade… You must never lose faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

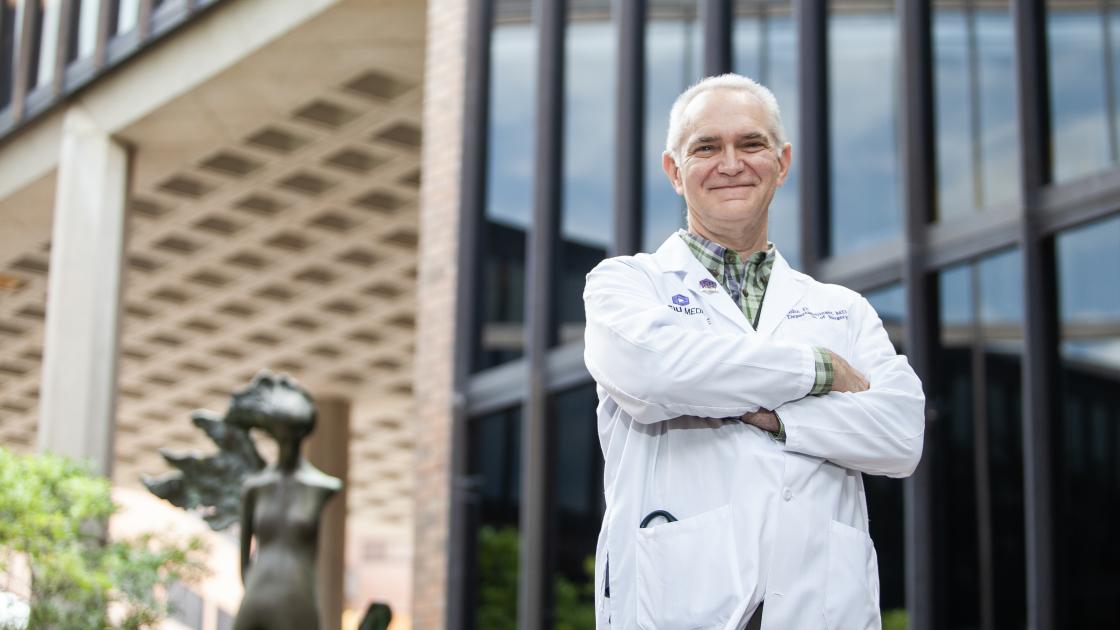

One of our key school symbols is the “Harbinger of Good Will” statue in the 801 building courtyard. In the sculptor, Kenneth Ryden’s own words, it “represents the many aspects of medicine… offering dignity, hope, and good will, and the figure itself symbolizes the spiritual essence of humanity.” This brief reflection is offered with gratitude for each of our lives and contributions, and a prayer that each of you, and together all of us, would embody such hope for our community, region and world, and for one another, for a time such as this. Peace, strength, and daily joy to each of you as you serve!