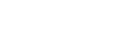

Resilient Survivor

Aspects Volume 38 No. 4

Written by Rebecca Budde • Photography by Jason Johnson

"The doctor told my parents that it was unlikely that I'd live through the night." Thereasa Abrams, PhD, LCSW, was only 6 years old.

It was a hot July day, and Teri and two of her siblings planned to fight boredom by melting a crayon in the small fire her brother had made in the open-faced charcoal grill. As the youngest of four siblings, Teri had the duty of sneaking into the house and past her mother who was tending to her oldest sister and grab the "evidence" unseen. Mission accomplished, she clutched a green crayon in her hand while she waited with her older sister next to the grill where the little fire burned.

"The last thing I remember is my 11-year-old brother coming out of the garage door with a tin can filled with gasoline," Dr. Abrams says. "The fumes were on me, and when he threw the cup of gas into the grill, the fire hit me in the face. I didn't stop, drop and roll. I don't remember running either, but I did. I was like a little fireball running around the yard."

Dr. Abrams' mother heard the screams from inside, grabbed a towel from the clothesline to smother the flames as her brother tackled her to the ground. She sustained second- and third- degree burns over approximately one-third of her body, mainly her face, back and limbs.

The memories have become fuzzy, like a dream: The charred, gray skin on her right hand lifted away like the layers of a newspaper, but she didn't recognize the hand as belonging to her. The faces of her siblings looked horrified. Screams echoed, but she wasn't sure whose screams they were. Next was a long car ride, extreme thirst and a kind person behind a white hospital mask promising to get her a drink of water.

It was about a 30-minute drive from her family's home in a small Michigan farming community where her father owned a dry goods store to the hospital in Kalamazoo. The hospital did not have a burn unit, but Dr. Abrams and her family were fortunate to have someone who knew how to help her. "A plastic surgeon who specialized in burns had just come there; I was so fortunate that he was new, he had time, and he invested it in me," she says gratefully so many years later.

Her reconstructive surgeries began about a month after the accident and continued through high school. "I've lost track of how many I've had," she says. The majority of the surgeries were for her face. The red, twisted scars associated with burns softened. "My doctor understood that he was shaping my future with these surgeries," Dr. Abrams says. "He was artistic and took the contours of my face into account." Though she's been told that her scars are barely visible, she feels awkward receiving the compliment, an indication that the effects of her injury go deeper.

In addition to the pain of surgery and healing of the burns, 6-year-old Teri endured two months of isolation to reduce the risk of infection. "My parents could only sit outside my room," she says. They took shifts driving back and forth to stay with her at all times, except in the wee hours of the night. Approximately three-and-a-half months after the accident, she returned home.

Times were tough after the accident, but Teri says she felt accepted in her home community. But, moving to new community in her pre-teens, Teri lost her protective environment. "It was rough; burns are uncommon and the scars often frighten people." She learned to adapt and, like many others, Teri spent her teens and twenties trying to find her path.

"I was 30 years old before I met another burn survivor." At a burn support group in her Milwaukee community she also first learned the term "burn survivor" and began to become familiar with a common thread in the dispositions of those she met. "I've met hundreds of burn survivors now, and they all seem to have this resilience and sense of freedom. They're spared the idea that life is safe and predictable; they know life can change in an instant, sometimes by no fault of their own. Because of that, they want to seize the day, but there's also a great need for building confidence."

This commonality was intriguing to Teri as she continued her involvement through the Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors, an international peer support group for survivors and their families. When she moved to New York in 1989, she began a support group at Strong Memorial Hospital, the same hospital where Alan Breslau, the founder of the Phoenix Society was treated for his burns in 1963.

Recognizing the strength of her supportive and empathetic nature, Teri later moved to Carbondale where she received her bachelor's and master's degrees in social work. But she couldn't find any burn units willing to hire a social worker, so she began work in the mental health field while raising her three children. "I had always planned to go back to a burn unit to work," Teri says.

Her resilience endured and she found her path back to helping burn survivors.

In 2009 she began formal research for her doctorate of health education on the unique resilience that carries survivors through the acute phase of burn treatment and supports them through healing and future health. "During the years of working with burn survivors, I came to observe the same kind of resilience in other burn survivors that I felt within myself," she says. "It wasn't until I started the research for my PhD that I was able to understand and put words to the benefit of supporting and encouraging the resilience in patients coming out of the burn unit. I wish I could have gotten that support earlier."

After receiving her doctorate, Dr. Abrams joined the SIU School of Medicine staff as assistant professor of in the division of plastic surgery. Seeing a need for the region, she began a burn survivors and family support group in partnership with Memorial Medical Center's Regional Burn Center. She offers a calming presence to family members of patients in the burn unit when she visits to offer peer support. "It's really important when it comes to burn injuries that the family have support," Dr. Abrams says. "If they want to talk or ask questions ñ most don't know much about being burned ñ so I can answer them from what I know."

Her current project involves the development of mobile application content to help burn patients who are leaving the burn unit heal physically and emotionally.

"I'm a problem solver," Dr. Abrams asserts. "A lot of why I want to help deals with my own insecurities of not feeling good enough, even though inside of me, I feel like I can do anything. It's a weird paradox. I want to help people maximize their future faster than I did ñ I got such a slow start."