Studying a biological switch

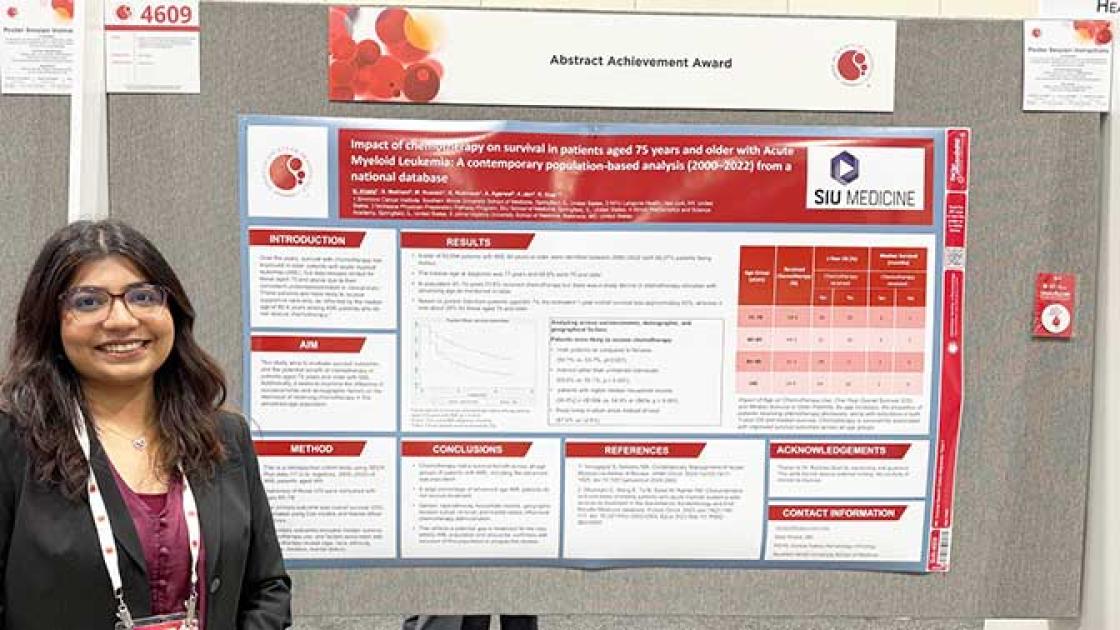

Dr. Andrew Wilber’s efforts to restore healthy hemoglobin to diseased red blood cells

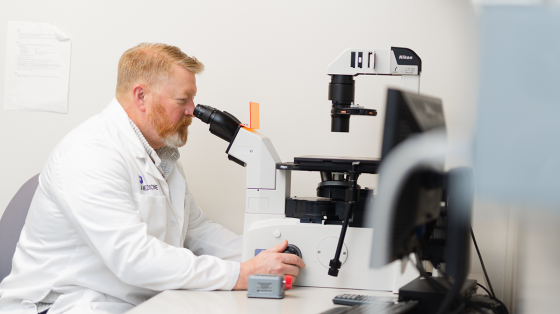

SIU researcher Andrew Wilber, PhD, is advancing new gene therapies for people living with sickle cell disease and β(beta)-thalassemia.

These genetic disorders result when a child inherits an altered version of the β(beta)-globin gene from both parents. This leads to a defect or deficiency in hemoglobin produced by red blood cells.

Unlocking secrets at the cellular level fascinates Wilber. The central Illinois native joined SIU School of Medicine in 2008 after completing a PhD in Molecular Genetics at the University of Minnesota and a fellowship in Experimental Hematology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. He is now an associate professor of medical microbiology, immunology and cell biology, splitting his time between scientific research and teaching.

His career has been focused on answering relatively straightforward but powerful questions, often dealing with intractable, inherited illnesses. “How can we address this critical issue?” asked Wilber. “That is what interests me as a scientist and educator.”

Searching for the switch

Hemoglobin is the molecule that red blood cells use to transport oxygen from the lungs to our body’s cells and tissues, as well as carry carbon dioxide waste back to the lungs, where it is exhaled. Wilber’s research focuses on the severe hemoglobin disorders, sickle cell disease and β(beta)-thalassemia.

In those patients, a genetic defect disrupts the instructions for making a healthy version or level of the β(beta)-globin protein, a key component of adult hemoglobin. Patients diagnosed with either disorder must receive frequent blood transfusions. While helpful, this option causes iron levels to rise, requiring additional treatment to remove it.

Medicines haven’t helped those stricken with the condition. Bone marrow transplant have been more effective, but are only available to patients with a suitable, matched donor. As a result, gene therapies have been gaining traction, with some receiving FDA approval.

Newborn babies produce fetal hemoglobin that gets turned off and replaced by adult hemoglobin during the first year of life. Wilber’s lab is studying the “switch” that causes hemoglobin production to transition from the fetal-type to adult-type – and how to reverse it. For patients with these diseases, that switch triggers symptoms that include anemia, fatigue, severe pain episodes or stroke.

Remarkably, a small number of people who inherit the genetic changes that cause sickle cell disease or β(beta)-thalassemia have no idea they have the disease because fetal hemoglobin continues to be produced into adulthood. By understanding how the switch occurs, Wilber’s team is exploring ways to revert hemoglobin back to its healthy fetal state and relieve the symptoms of both disorders.

His efforts have led to a pair of promising discoveries. The group found a noncoding RNA molecule that helps red blood cells survive, and an mRNA-binding protein that can shift hemoglobin production in adult red blood cells back to the fetal type. Their findings pushed the science forward and are laying a foundation for potential future therapies.

Moving from bench to patient

As an alternative to reversing hemoglobin production, Wilber’s lab is partnering with San Rocco Therapeutics, and Frank Park, PhD, at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy to develop a therapy that can deliver a healthy version of β(beta)-globin into a patient’s blood cells. The therapy uses immature stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow that have the ability to become all types of cells, including red blood cells. Once onboard, the new β(beta)-globin will compensate for its defective or deficient version.

If successful, the procedure eliminates the need for future blood transfusions and effectively cures the patient. “The person can go on to experience a healthy, symptom-free life,” Wilber said.

Gene therapy to improve hemoglobin has been studied since the early 1990s, and an FDA-approved treatment for severe hemoglobin disorders was approved 2024. However, the high cost—in excess of $2 million per treatment—has limited widespread adoption. Wilber and his colleagues are committed to developing a best-in-class therapy with reduced costs and treatment times for patients. Their drug is named MiNiRoLu.

“Even though we are not the first-to-market, we believe our improvements could represent a safer and more effective therapy at a lower cost to patients,” Wilber said.

The next test is a controlled clinical trial to determine safety of this approach. Wilber and his collaborators are working through the regulatory process in both Europe and the United States to move the therapy into clinics for testing. If approved, patient enrollment could begin in late 2026.

"The innovative approaches coming out of Dr. Wilber’s lab demonstrate how transformative research can be," said Don Torry, associate dean for research at SIU School of Medicine. "By understanding the biology at its most fundamental level, his team is opening the door to therapies that could redefine the treatment of inherited blood disorders. Advancing science, developing life-changing therapies, and training the next generation of scientific leaders clearly exemplifies the mission of SIU School of Medicine."

Nurturing hope and the next generation of scientists

Wilber has trained more than 80 students during his career at SIU, from high school interns and undergraduates to medical students and graduate scholars. Through his teaching, he ensures that students and medical trainees in Illinois see and contribute to real science. He has earned multiple awards for teaching and has directed both the Public Health Laboratory Science master’s program; the Medical School’s Hematology, Immunology & Infection unit; and graduate concentration in Cell Biology, Immunology and Cancer Biology.

Wilber has some sage advice for aspiring researchers: “Do not fear failure,” he said. “Even when an experiment doesn’t work as expected, you can still learn something important.” In Wilber’s lab, a failed hypothesis is not viewed as a mistake, but as a stepping stone. Each impasse teaches him and his team something new about the work ahead. His work embodies the school’s mission: advancing science, training future generations and making real health care breakthroughs accessible in Illinois.

Wilber is fueled by a fundamental love of discovery, and what it can reveal. “These questions may look simple on paper,” he said, “but solving them can change lives.”

For patients grappling with the burdens of inherited blood disorders, the hope he is building grows stronger with each successful study.