A Unifying Approach

written by Steve Sandstrom

The minister fixed his gaze on the Sunday morning congregation. In a firm baritone, he said, “In the old days, mapmakers would sometimes mark the margins outside of the known areas with the statement, ‘Beyond this, there be monsters.’”

He stepped from behind the pulpit. “What they were trying to say is, ‘We only know so much. And you should only go as far as we know. So stay within the boundaries.’”

“But sometimes we do things that are dangerous, and there are problems that threaten our daily life,” he said, pacing across the stage as he spoke. “So you’ve got to have faith. You’ve got to have focus. You’ve got to have firmness. And you’ve got to have the foresight to know that there is something down the road that is bigger than you.”

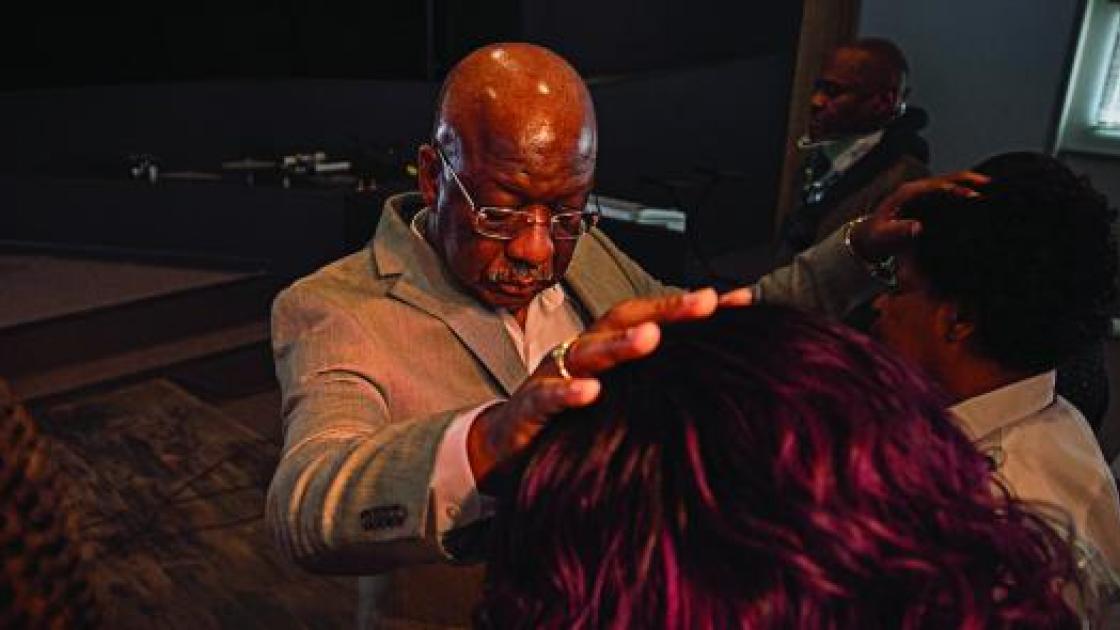

The words of Dr. Wesley Robinson-McNeese, pastor of the New Mission Church of God in Springfield, are also descriptive of Dr. Wesley Robinson-McNeese, associate dean for diversity and inclusion at SIU School of Medicine and an associate professor of internal medicine and medical humanities. Raised in East St. Louis, Dr. McNeese has led a rags-to-riches life that could inspire anyone, but especially those who may face adversity because of their diversity.

Dean and Provost Jerry Kruse, MD, MSPH, is a fan. “Dr. McNeese has made a significant impact on the diversity of our student body and learners, our faculty and our staff, and he’s been a champion for issues related to equity and inclusivity at Southern Illinois University and our community,” he says.

“The next generation of physicians will be better prepared to meet the needs of our region and medically vulnerable populations thanks to him.”

Early influences

Dr. McNeese joined the SIU faculty in 2001 to help launch the Office of Diversity Multicultural and Minority Affairs. With determination and an innate desire to help others, his efforts have paid off handsomely. He is preparing to step down from his position as associate dean in the summer and move into a new role to broaden diversity and inclusion programs across the SIU System.

It has been a journey that often took him outside the boundaries and into uncharted waters.

Dr. McNeese’s youth was spent learning and playing in the hard-scrabble streets of East St. Louis and the churches where his father, Timmie McNeese, preached.

One of eight children, Dr. McNeese did any job within the church that needed doing. He credits his father for instilling a strong work ethic, trying to keep the family fed, and with his interests in the ministry and community outreach. “It was fairly idyllic,” he says. “Even though we lived in a ghetto, so did everyone else we knew, so I didn’t know any difference. There were neighborhoods and families, and it was a time when it took a village to raise a child, which they did quite well.”

One of eight children, Dr. McNeese did any job within the church that needed doing. He credits his father for instilling a strong work ethic, trying to keep the family fed, and with his interests in the ministry and community outreach. “It was fairly idyllic,” he says. “Even though we lived in a ghetto, so did everyone else we knew, so I didn’t know any difference. There were neighborhoods and families, and it was a time when it took a village to raise a child, which they did quite well.”

Graduating high school in the mid-‘60s, he gave college a try but found it wasn’t a good fit. In 1966, he decided to enlist in the Air Force, and was shipped off to Vietnam in 1968. He considers himself fortunate. “I wasn’t what we called a ground-pounder; I wasn’t out in the bush. I was on base, listening to Morse transmissions. But there was constant shelling. I’m just thankful that I made it through.”

Back home, Dr. McNeese found employment at The Crusader, the weekly newspaper in East St. Louis. He started as the janitor and worked his way up to editor. More fortuitously, he met his wife LaVern, who was hired as a journalist.

A second job as a paramedic in the military reserves helped pay the bills, but his lack of a college degree stymied media pursuits across the river in St. Louis. Dr. McNeese decided to enroll in classes at Anderson (Ind.) University, and he and LaVern started a family. As a new student and father, he looked for a job that allowed him to work nights while attending school. His background as a paramedic helped him get hired as a hospital orderly. Within months he was in a plum job in the emergency department, “and that’s where I fell in love with medicine,” he says.

At the age of 30, Dr. McNeese enrolled at Illinois State University in Bloomington to better prepare for his next career path. An ISU chemistry professor told him about a program in Carbondale called MEDPREP where he could increase the odds of medical school admission. “At the time they accepted undergrads—it’s now post-baccalaureate—so in 1979, I was taking classes on SIU’s main campus in addition to my MEDPREP classes.” He remembers it as a very nurturing place: a small group of people, all in the same boat, trying to get into medical school.

And it worked. He was accepted into the SIU School of Medicine in 1982.

The science courses were tough, he recalls, but overall he thrived. “I just had to study hard and come to class, and I knew I ultimately would become a physician. After everything else that I had done with my life, this seemed fairly simple.”

One of five minorities in his class of 70 students, Dr. McNeese recognizes that his time in medical school was somewhat unique. “I had 10 years on nearly everyone else in the class and was a no-nonsense kind of guy, so I had some leadership skills,” he says. “I got along well with my classmates. I had my wife and my kids here, and this was a good place, then and now.” When classmates talked to him about being class president, he was open to the idea. “I’m very proud to be the first African-American student to serve as class president during all four years here,” he says.

In his role as executive assistant to the dean for diversity, Dr. McNeese has heard from some African-American SOM graduates who have very different memories of their time here. “Many of them had awful experiences, so much so that they don’t want anything to do with the school.”

“Then I meet others who had an experience more similar to mine where it was just great. I come away from that believing that a medical school experience is very individualistic. The outcome is certainly colored by those who guide and teach, but it also depends on what you bring into it.”

In his fourth year as a student, Dr. McNeese did an away rotation in emergency medicine at Northwestern University in Evanston. It became his top choice for Match Day. “I never thought in a million years I’d get back there. But they picked me. And the kinds of things they were doing were amazing. I loved the city and the variety of things to do. It was probably one of the best experiences of my life.”

In his fourth year as a student, Dr. McNeese did an away rotation in emergency medicine at Northwestern University in Evanston. It became his top choice for Match Day. “I never thought in a million years I’d get back there. But they picked me. And the kinds of things they were doing were amazing. I loved the city and the variety of things to do. It was probably one of the best experiences of my life.”

But when it came time to settle down and raise his growing family, he opted for something more suburban. In 1990, he began work at Kankakee’s Riverside Medical Center and served as a quality improvement director (1990-2001) and associate director of emergency medicine (1994-2001). After a decade of work as an emergency physician, Dr. McNeese was again ready for a change. In 2001, he had an epiphany about coming back to the church. “The people at Anderson College had told me I was destined to be a minister, but I ignored that; I was going to be a physician.” Some of his spiritual mentors suggested he return to Springfield, where a pulpit was open.

The School of Medicine’s second dean, Dr. Carl Getto, heard Dr. McNeese was back in town. “He was on the board of directors for the Urban League at the time,” Dr. McNeese says. “He was very concerned with the declining number of minorities on campus,” a pattern that was typical of US medical schools at the time. “He wanted to know if I was interested in the new post of executive assistant to the dean for diversity, multicultural and minority affairs. I was definitely interested; being a minister didn’t pay much.”

Dr. McNeese was soon back to working two jobs: one to enrich his soul and one that would ultimately enrich his alma mater.

“To be effective, both require a great deal of content knowledge and research,” he says, “but one is very down to earth and usually pedantic, while the other allows you to float wherever the spirit leads you, elaborating and creating as you go.”

Underrepresented

Because there weren’t a lot of diversity recruitment programs to model from, Dr. McNeese began a “listening tour” to tackle the charge. “I talked with African-American students, faculty and staff to see what issues they had that led to this situation. Then I started addressing the issues.” Dr. McNeese immersed himself in the process, meeting people, attending workshops and classes, and began to integrate what he learned into the school’s practices.

One cannot turn around a trend overnight. With support from J. Kevin Dorsey, MD, PhD, SIU’s dean and provost from 2002-2015, Dr. McNeese approached it with a persistent professionalism that he’d learned as a soldier and a student.

Over a 15-year span, he created and organized numerous initiatives to promote and expand the culture of diversity and inclusion at the school. Most notably, the “P4”—the Physician Pipeline Preparatory Program—to encourage high school students to pursue careers in medicine. He also spearheaded Diversity Week, the Eastside Health Initiative, the Metro-East Healthcare Elective, and the Alonzo H. Kenniebrew Forum. Jeanne Kohler, PhD, is an assistant professor of medical education at SIU and director of the Academy for Scholarship in Education. She considers Dr. McNeese to be a role model. “When we first met to discuss the Pipeline Program, he began sharing the program and his commitment, and I knew I’d found another innovative educator,” she says. “It was clear he was working to create learning environments for young people who are often funneled out of science, to grow and thrive.”

Per Dr. Getto’s initial charge, Dr. McNeese has initiated recruitment efforts of medical students, faculty and staff and started a faculty mentoring program. The results are apparent in the offices and corridors of the university. According to the most recent study by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), SIU School of Medicine ranks in the 96th percentile of recent graduates who are black or African-American. It ranked in the 83rd percentile for women faculty, and in the 57th percentile for underrepresented minority faculty members.

The improved numbers translate into greater opportunities for members of groups that were previously marginalized. Lives have been changed for the better, and Dr. McNeese is rightfully proud. “I know the school was struggling with attracting people from underrepresented groups; now we’re not. We’ve reached critical mass and we’re holding it.”

Dr. Alicia Altheimer, a second-year resident at SIU Family Medicine, knew she wanted to come to SIU after meeting with Dr. McNeese during student interviews. “He made me feel so welcomed, and he made me feel that the school really wanted me to be here. And he was monumental in advising me throughout my time as a student,” she says. “His encouragement, advice and prayers kept me motivated during difficult times in my medical school career.”

Dr. McNeese is now preparing for the next crossroads in an illustrious career. On June 30, he is stepping down as associate dean for diversity to take on a new role that SIU System President Randy Dunn has established: internal consultant and system executive director for diversity initiatives. He will help to coordinate the implementation of a dozen initiatives to advance awareness-building and cultural competency across all SIU campuses.

Forging paths is not new to Dr. McNeese. It should feel like familiar turf to the boy rooted in southern Illinois who’s looking toward the next big challenge.

“At SIU I got to be a trailblazer and establish some very good programs,” he says. “Becoming the first associate dean for diversity and inclusion is a crowning achievement. But more importantly it’s laid the foundation for whoever comes after me.”

“Now they can really do something special.”